T H E E A R L Y 1 5 T H C E N T U R Y

|

THE PERIOD of most intense development of the sailing ship got underway with the reinstatement of the perpendicular square sail to the Mediterranean in the mid-14th Century. Having been almost completely replaced in the Mediterranean by the triangular, fore-and-aft (longitudinal) lateen sail for a thousand years, the square sail was alive and well with the Northern European craft like cogs, and their appearance to the Mediterranean with the Crusades gave the impetus to start building similar ships there.

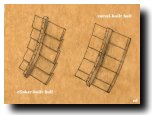

clinker- and carvel-built hulls The main difference between the North-European and Mediterranean ships was their method of hull building. The northern ships were clinker-built, with the hull outer surface planking overlapping, creating a jagged surface, whereas the Mediterranean hulls were carvel-built, with flush, even planking. As the ships' size increased in the 15th Century, the clinkerbuilt hull was found to be unsuitable as it wasn't tight enough -- the largest clinker built ship, the English Grace Dieu (1418) was a failure, and signalled the end of the building method in favour of the carvel-built hull.

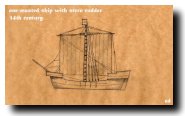

one-masted ship Until the 15th Century, the square-rigged ships mainly carried one mast with one sail, just like the North-European craft did. They were built with castles, attached superstructures rising above the stem (forecastle) and stern (aftcastle) of the ship and used, as their name indicated, as defensive/offensive positions in naval battles. They also offered more space aboard and started the development to differentiated stern quarters for the officers. The large main sail was attached to a horizontal yard that could be raised and lowered, as well as swivelled around by the mast by braces, lines attached to the ends of the yard, on freely-moving collars, parrels. Although the square sail offered good propulsive power while sailing before the wind, it was cumbersome and ineffective in head wind. For handling of the sail, bowlines from the leechs, the sides, of a sail led to the bowsprit that stuck out from the forecastle. The top or crow's nest atop the mast had been an old feature of the Mediterranean ship, but it would develop considerably in the next centuries as a lookout place and a battle top for bowmen and sharpshooters.

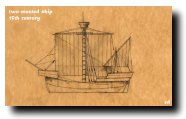

two-masted ship There had been examples of an additional mast raised above the aftcastle as early as the late-14th Century, but not until the 15th Century did these installations become common. The second mast carried a lateen sail, the mizzen, taken straight from the traditional Mediterranean craft. The new sail helped to steer the ship and, at least somewhat, to tack it more easily against the wind. By this time, the appearance of the ship already resembled a carrack.

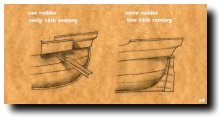

rudders Another addition to the Mediterranean ship was the installation of the rudder to the sternpost (in the Northern Europe the method had been in use since the early 13th Century). Previously, there had been separate, oar-like rudders hung from the sides of the ship -- now a single rudder was attached to the rudderpost and controlled by a lever -- as the ships grew in size, the helmsman had to steer from underneath the deck according to shouted commands. Nevertheless, the steering of a sailing ship continued to be equally an orchestrated effort of the helmsman and the crewmen handling the sails, and that continued (and continues) to be the fact 'til the last sailing ship. |

ENTRANCE THE TWO-MASTED SHIP THE CARRACK THE GALLEON

|

text and drawings © e t dankwa 25 December 1999

|