T H E M I D - 1 5 T H C E N T U R Y

|

THE CARRACK is the ship type that truly starts our little excursion into the past of the full-rigged ship. Not only did it for the first time incorporate the castle structures into the hull, but it also already had all the basic rigging elements that were expanded along the upcoming centuries. Specific features of the carrack were its rounded stern, with the planks curving around from the sides to the rudderpost, the forecastle located directly above the stem, with the bowsprit rising from its top -- an arrangement that had been unaltered since the first "battlements" had been installed on the bow of a sailing warship -- and the aftcastle that formed an integral part of the hull. The carrack (called "nao", for "ship", by the Portuguese) was the definitive beast of burden of the Age of Exploration; Magellan, for example, had an all-carrack fleet with which he set to circumnavigate the globe in 1519. The spacious vessels offered room for a large crew and provisions -- as well as for cargo to be brought back home.

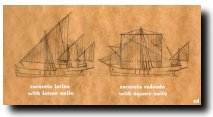

caravel latina and redonda Another ship widely used in exploration was the lateen-rigged caravel, or caravela latina and many were modified as square-rigged ships, caravela redondas, to take advantage of the fair wind -- for example, both of Christopher Columbus' caravels of his 1492 voyage ended up as square-riggers. The shallower hull and better lines of the caravel made them ideal for these long voyages as they were inherently better sailers than the rolling, bulky carracks, albeit their characteristics also meant smaller carrying capacity. The rigging underwent an extensive expansion: The mainsail grew in size and there was often an additional sheet line connected to the middle of the sail foot in addition to the lower corners, clews. Moreover, one or two detachable parts called bonnets were often added to the bottom of the main sail, to be removed when wind speeds increased too high.

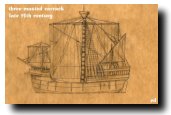

three-masted carrack A third mast, the foremast with the foresail, was first developed more as an aid in ship steering than as a propulsive unit in itself. Later the sail and the mast grew in size and became a similar part of the full rigging to the mainsail. An additional sail, the spritsail was bended to a yard under the bowsprit. The sail was called "blinda" in Germanic languages, which reflected the fact that the sail effectively prevented visibility forward. A new sail, the topsail emerged above the mainsail in the late 15th Century, first as a small yard and sail on the flagstaff rising from the top, then as a full-sized sail on its own mast attached to the mainmast. Later, also the foremast got its topsail. By the end of the reign of the carrack, a third sail, the topgallant sail had appeared in some ships above the topsail in its topgallant mast.

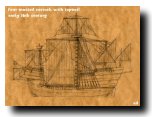

four-masted carrack A new fourth mast, the bonaventure, was erected in some larger ships behind the mizzen mast, carrying a lateen sail, the bonaventure mizzen. Later, lateen topsails and even topgallant sails were added atop the mizzen masts, although their practicality was doubtful, and they must have been seldom used. Another addition to the Mediterranean ship were the ratlines, the horizontal "ladders" attached to the shrouds which supported the masts from the sides. Although ratlines had been present in the Northern European ships for over two centuries, in the Mediterranean ships they had been so far replaced by a rope ladder. As the rigging developed with more mast and sails, also the size of carracks increased. Giant 16th Century warships such as the Portuguese Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai or Henry VIII's (the creator of the Royal Navy) regal namesake Henry Grâce à Dieu (1514) -- more "commonly" known as "Great Harry" -- and Mary Rose (1510, refitted in 1536) were examples of such, almost lavish, undertakings that the new technology allowed. The latters, with their bronze cannons on several decks and their flat sterns, were, despite the towering castles, prototypes for the future's gun-armed galleons. The introduction of cast-iron as the material of heavy guns (replacing wrought iron pieces joined together), along with the replacement of breech-loaded guns on fixed mounts with mouth-loaded on wheeled trucks in the mid-16th Century brought better "predictability" to the behaviour of guns. The use of hinged gun ports from the early 16th Century on allowed the placement of guns into the lower decks, near waterline, thus increasing the number of cannon aboard. These innovations made the concept of a heavy-gun warship a reality. The large superstructures of the carracks, however, affected the use of rigging and thus their sailing characteristics: the towering castles made the ship top-heavy and more prone to topple in strong winds -- what actually happened to Mary Rose in 1545, when burdened with excess load -- that limited the actually usable sail area. The large superstructures also caused wind drag as the ship sailed, and could reduce the wind hitting the courses, or lower sails, ie. the mainsail and foresail. Nevertheless, Columbus' diminutive flagship Santa Maria still remained undoubtedly the world's most famous carrack. |

ENTRANCE THE TWO-MASTED SHIP THE CARRACK THE GALLEON

|

text and drawings © e t dankwa 25 December 1999

|