T H E M I D - 1 6 T H C E N T U R Y

|

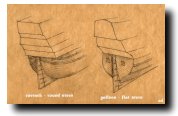

THE INEFFICIENT hull form of the carrack was one of the reasons that the galleon ship type took the dominant role in shipping by the end of the 16th Century. The new hull form that offered a considerably greater hull length-to-keel length-to-beam (width) ratio (4:3:1 as opposed to the carrack's 3:2:1) improved the flow of water around the hull, reducing resistance and giving the ship more manoeuverability and better seaworthiness. Also carrack's round stern was changed into a narrower, flat one that also supported the weight of the aftcastle better.

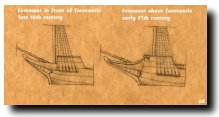

carrack and galleon sterns The excessive bulk of the fore- and aftcastles in the later carracks had hindered their sailing characteristics. That was also characteristical of the first galleons, albeit the moving of the forecastle from above the stem to a position behind it, with the bowsprit poking out from its front, reduced the chance of wind hitting the forecastle and turning the ship inadvertently. That enabled a galleon to sail considerably closer to the wind. A new addition, the head was constructed to start from the front of the forecastle (and above the stem) and to extend out underneath the bowsprit in a tapering form to a decorated figurehead. This area was used for the crew's toilets and even in today's mariner language the word "head" means a toilet...

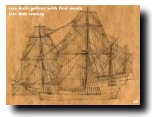

race-built galleon

The introduction of the modified galleons with the

Revenge in 1575 moved the mobility of sailing warships to

a new level. The English galleons, with their smaller size, lower

superstructures (older ships with tall castles were cut of their

excess bulk, ie. "razed", thus the name "race-built"), longer and

slimmer hulls and improved rigging, as well as improved long-range

gunnery (the Spanish still relied on closing on the enemy and boarding

them -- a tactic deriving all the way from the Roman navy -- which

required great manpower aboard, hence a large, unmanouverable ship as

well as old-style large castles to rain fire on the opponents' decks)

could out-sail and out-gun their more cumbersome opponents, making them

unable to even try to board. The English used their ships to

advantage when they fought off the Spanish Armada in 1588. The addition of ever-heavier cannon, as well as the need to otherwise increase the cargo capacity of the ships, led to the use of hull frames that were wide at the waterline, but tapered inward in order to take the guns on the sides as close to the centreline as possible and thus improve the stability of the ship (the tapering form also had the added advantage of making boarding the ship more difficult from an adjacent enemy ship). Especially the Dutch also had ships with a considerably flat bottom in order to make them fit for sailing in the shallow coastal waters of Holland.

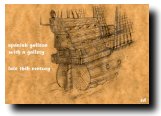

gallery On the stern side, galleries, open-air balconies that went around the whole stern portion, extending on occassions even to the mainmast chains (where the shrouds were attached on the hull) on the sides, were introduced especially in larger galleons. Later, the galleries were at least partially covered, a development started with the Dutch ships. As covered, they became the officers' toilets and later a part of the officers' quarters. The galleries would remain a distinctive part of the stern of the sailing ship long into the 19th Century. The introduction of a vertical lever for operating the long rudder bar and an opening for the helmsman to see the sails helped the steering operation considerably. Gradually, the steering lever would be extended to the deck and, in the 18th Century, replaced by a wheel which offered better maneuverability, and which has been retained to the present day. As for rigging development in the era, one important change, first employed by the English Navy, was the recutting of the large, billowing sails into flatter ones to improve the sailing capabilities and make the ships sail better into the wind. The use of bonnets under the sails was spread to the foresail and (lower) mizzens. The Dutch introduced around in 1570 the first topmasts that could be lowered, ie. slid down along the lower mast so that the two stood adjacent above the deck. This innovation quickly spread to other countries and eventually the topsail began to grow in size while the courses got lower and smaller.

foremast In the beginning of the 17th Century, the foremast, which had been so far located in front of the forecastle, was moved back and raised now through the forecastle top deck.

mizzen topsail and sprit-topsail Around in 1620 a square topsail, the mizzen topsail, was introduced to the mizzenmast above the lateen mizzen, replacing the unpractical lateen sail. This resulted in such ships being called frigates (not to be confused with the term of the same name that meant a sailing warship with one full gun deck). At the same time the still high-rising aftcastles of the large ships led to a need for more sails to the bow of the ship. A new mast with a square-sail, sprit-topsail, was derived from a flagstaff at the end of the bowsprit. Although awkward in use, the sail nevertheless remained until the advent of jibs to the foremast stays. Also a top was introduced to the end of bowsprit -- there had already been tops in virtually every mast, at the top of individual mast segments, bar the topmost, of course. As with the flamboyant carracks, also the galleons were adopted to the "prestige ship" role. The French Saint Louis (built in Holland in 1626 as an example for the new expanding French Navy) and the Swedish Vasan (1627) were both constructed with the help of Dutch naval engineering knowledge (also Russians, Germans and Danes used the Dutch expertise), whereas the English Prince Royal was built by the master shipwright Phineas Pett in 1610. All three were equipped with a large number of cannon, as well as ample decor and sculptures. The number of heavy cannon may well have been Vasan's undone: the top-heavy ship sank shortly after it had set sail for its maiden voyage in 1628, but it was recovered 333 years later, in a relatively good condition, restored, and put to display in a dedicated museum. The form and general appearance of the square-rigged sailing ship of the latter centuries has been more or less derived straight from the galleon -- there have of course been modifications in general arrangements, structures and rigging, but the form with its castles, the poking head and the arrangement of masts and their functions survived to the last of the full-riggers. |

ENTRANCE THE TWO-MASTED SHIP THE CARRACK THE GALLEON

|

text and drawings © e t dankwa 25 December 1999

|